”I pray you have the bodies of our Massachusetts soldiers, dead in battle, to be immediately laid out, preserved in ice and tenderly sent forward by express to me. All expenses will be paid by this Commonwealth.” – Governor John Albion Andrew, Massachusetts

Just days after President Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 troops to suppress the rebellion of seceded southern states, the streets of Baltimore descended into violence. From the north they came, overland along the dusty, rutted roads and along the Northern Central, and Philadelphia, Wilmington, & Baltimore Railroads, the hastily organized, mostly untrained militias who answered Lincoln’s call to arms. Among them were the boys of the 6th Massachusetts Infantry.

Arriving at the President Street Station at around 10am, the process of decoupling the cars had just begun – cars would be individually pulled by horses along Pratt Street to Camden Station as city ordinances forbade locomotives within the city proper – when crowds began to assemble. As the crowds grew larger, they became more unruly and the situation tense. Four of the six cars made it through before the crowds blocked the last two by dumping timbers and anchors on the tracks.

About 250 Massachusetts men were then forced to march the route along Pratt St. two Camden Station. The mob quickly descended and began to hurl bricks and cobblestones, and “Queer Missiles” (Chamber Pots) with some brandishing pistols, and muskets. When the dust settled, four soldiers were killed with another thirty-six wounded. Twelve civilians were also killed, with dozens more wounded.

And thus, it was, one of the darkest days of the darkest periods in Baltimore’s and America’s history. But, Baltimore would one day see the 6th Massachusetts again, only this time, there would be cheerful crowds with all the pomp-and-circumstance one city could muster as they welcomed the boys from Massachusetts as they made their way south to Charleston, SC and on to Cuba to join America’s campaign to aid the Cuban struggle for independence from Spain and eventually the expulsion of Spanish colonialism in the Americas and Southeast Asia.

In May 1898, as the 6th Massachusetts was mustering in South Framingham, leading citizens of Baltimore endeavored to efface the foul memory of Baltimore’s reception of the Massachusetts regiment thirty-seven years before on that dreadful day in April 1861 by inviting them to parade through Baltimore to experience what the Baltimore Sun described would be a “lovefest.”

Telegrams were sent to Adjutant General Henry C. Corbin in Washington, Col. Charles F. Woodward, Commander of the 6th Regiment, and to Mayor Josiah Quincy of Boston extending the invitation and sincerest desire on the part of all of Baltimore to honor the 6th Massachusetts with a parade through the city.

The response from all corners was overwhelmingly positive and the Baltimore honor committee got to work.

As the 6th readied to embark for its train south, Gov. Roger Wolcott in address to them said,

“You are the direct heirs of the men who stood by the bridge at Concord and fired the shot heard round the world. You are the heirs of the men whose blood stained the streets of Baltimore, who today Thank God! are ready to greet a Massachusetts regiment with the full-hearted loyalty of a reunited nation.”

Reminiscent of the arrival in Apr 1861, the 6th would be met at the Mount Royal Station by Mayor William Malster and Police Marshall Samuel Hamilton. Then Mayor George Brown and Marshall George Kane met the first contingent northern militia (and federal troops) at the Bolton St. Station of the Northern Central Railroad the night before the riot of 19 Apr, in a successful attempt to protect them from the assembling crowd of southern sympathizers.

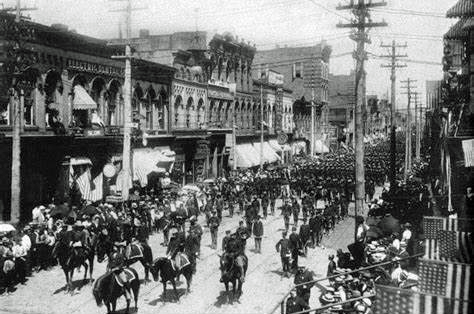

The 6th Massachusetts Regiment arrived in Baltimore on 21 May 1898 at approximately 4:30 in the evening. Once detrained, they marched towards Camden Station along Mount Royal Ave. to Charles St. to Monument St. and eventually on to Camden Station. All along the parade route were throngs of cheering crowds, pelted this time by flowers thrown by enthusiastic well-wishers. The men of the 6th were given box lunches, regaled by various bands with popular music, and as a heartfelt thank-you from the citizens of Baltimore, a souvenir badge with the Maryland State flag and an inscription that read, “Maryland to Massachusetts, 1898.”

Baltimore turned out en masse for the 6th Massachusetts and did its best to present itself as a city far removed from that dark day in Apr 1861, and one that stood solidly arm-in-arm with their fellow countrymen, as well as a city sincere in its intent on assuaging its guilt-by-participation in an even darker period in the nation’s history.