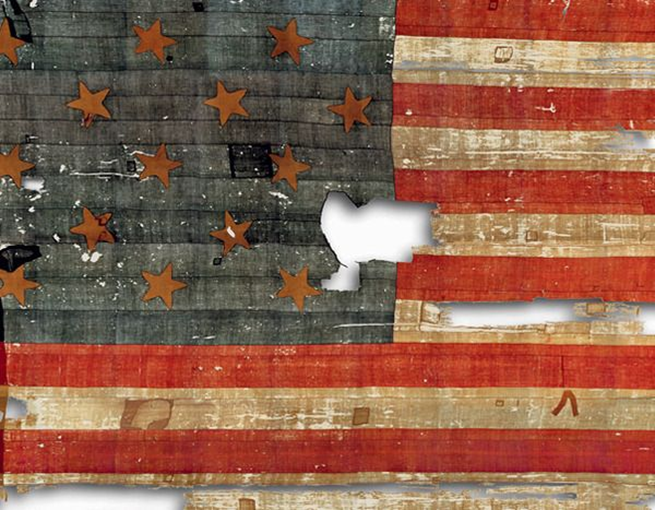

On display in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., is the historic “Garrison Flag” flag that flew over Fort McHenry during the Battle of Baltimore on Sept. 13 &14, 1814: the flag that would inspire Francis Scott Key to pen his iconic poem, “Defence of Fort M’Henry,” that would ultimately become our national anthem.

Or is it?

On the 25th of June 1878, a venerable old citizen of Baltimore named William McPherson passed away at the age of 83 at the Inn of his son-in-law in of Cockeysville, MD. Appearing in the Baltimore Sun on the 28th of June, William McPherson’s obituary and funeral notice gave rise to an enduring mystery concerning the very flag that had defied a twenty-five-hour onslaught by the British under Admiral Alexander Cochrane during a long, stormy night that saw 1500 cannonballs, shells, and rockets fired at Fort McHenry and its defenders.

After the war, McPherson would later claim that it was he who was in fact in possession of one of the most cherished icons of American resolve in the defense of freedom, “The Star-Spangled Banner.” According to his obituary, he claimed to be in possession of the flag since the battle and it was his wish to be buried with it and a British mortar shell that he had also acquired during the battle.

William McPherson was born in Baltimore in 1795, he would marry Eleanor Shock in 1818 and father at least three children but only one, Johanna, would survive to adulthood. Eleanor would die in August of 1848. William spent several years working for James Carroll, Jr. at his Mount Clare estate before moving into the mansion and caring for the house and grounds, known as “Mount Clare Gardens,” from about 1836 through early 1852.

Throughout the 1840s he would host gatherings and celebrations by various veteran associations on the grounds of Mount Clare, to include the National Encampment of the Veterans of the War of 1812 in May 1842. That encampment was attended by President Tyler, Chief of Staff Winfield Scott, Governor Thomas, and many other dignitaries along with surviving defenders of Baltimore, as well as troops from Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Washington DC.

According to available muster rolls and pension records, William McPherson served with the 38th US Infantry Regiment, Capt. Isaac Aldridge’s Company, under the command of Lt. Colonel William Steuart. He enlisted as a Private on 7 Feb 1814 and was discharged a Sgt. on or about the 6th of Apr 1815. Though it was reported in his obituary that he was a “Captain” in the regular army, that was incorrect. It may be that he was given the honorary title out of respect for his hosting and patriotic support of rendezvous and other similar events while at Mount Clare in the 1840s.

In the spring of 1814, the veteran 38th was positioned at Fort Covington (a mile west of Fort McHenry) and later, during the summer, on the lower Patuxent River with Commodore Joshua Barney’s Chesapeake Flotilla at the Battle of St. Leonard’s Creek.

In early Sept., the 38th Infantry was ordered to Fort McHenry and would be stationed in a “dry ditch” along with 600 other troops in support of artillery bastions outside and arching around the front of the fort. During the bombardment of Sept. 13-14, 1814, the 38th would see some of the heaviest of the onslaught and survive relatively intact, but for one notable casualty, a runaway mulatto slave from Prince George’s County named William Williams (alias Frederick Hall). After the battle, Lt. Col. Steuart and his men of the 38th would receive high praise from the fort’s commander, recently promoted Lt. Col. George Armistead, who reported, “…I found him vigilant and prompt, his company in a fine state of discipline – his conduct during the bombardment was such as to deserve [my] entire approbabtion (sic)…”

The “Garrison Flag”

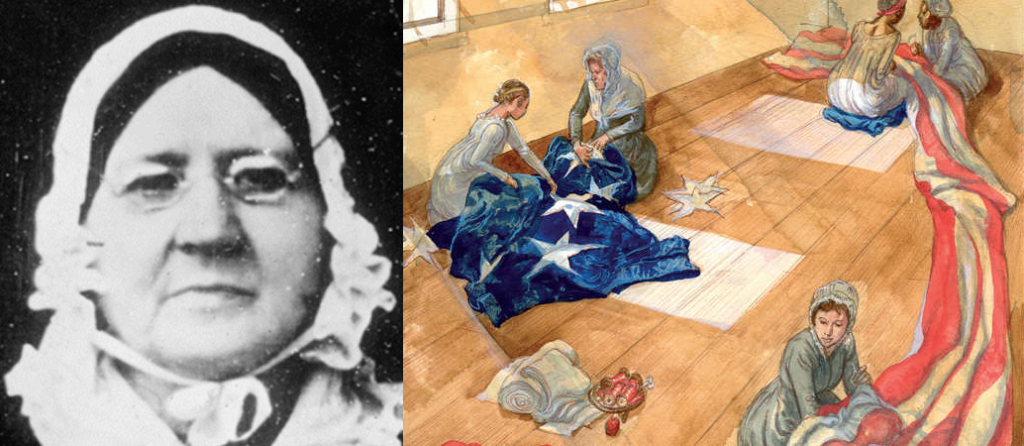

Taking command of Fort McHenry in June of 1814, Major George Armistead would soon commission Baltimore flag maker Mary Pickersgill to manufacture two new flags for the fort, a primary “Garrison Flag,” and a second “Storm or Foul Weather Flag” for use in inclement weather. Major Armistead wanted a flag “so large that the British will have no difficulty seeing it from a distance.”

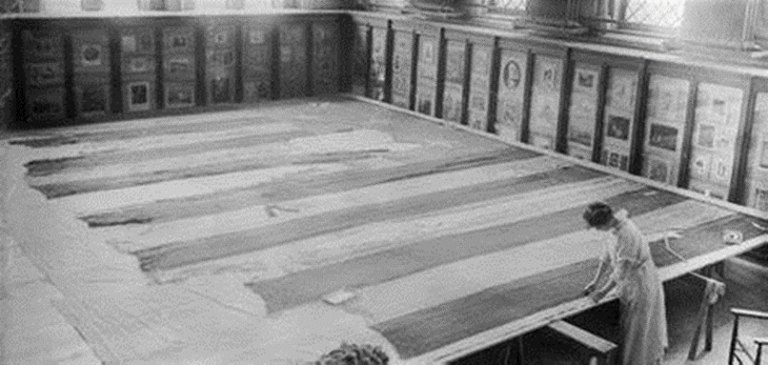

Mary Pickersgill received an order to sew two flags, a garrison flag measuring 30’ by 42’ and a flag to be used in foul weather that measured 17’ by 25.’ For these two flags, the government would pay her $405.90 and $168.54 respectively. The contract terms included a delivery timetable of within six to eight weeks. Mary would be assisted by her daughter Caroline along with two of her nieces, Eliza and Margaret Young, an indentured Black apprentice named Grace Wisher, and at times by her own mother, Rebecca Young, who taught her the art of flag making.

Mary and her assistants would stich the flag from a variety of dyed English wool bunting with the stars made from white cotton. The stripes were approximately 24” wide and the stars two feet in diameter. This flag, and the smaller foul weather flag would fly from the fort’s 90-foot-tall flagpole.

The British would launch their attack on Fort McHenry and Baltimore early in the morning of 13 Sept 1814, and would not let up until nearly 4am the following morning. Sgt William McPherson, his comrades in the 38th Infantry, and the entirety of the “Defenders of Fort McHenry” would prevail, forcing the withdraw of Admiral Cochrane and the British fleet soon after dawn. As the storms ceased just before dawn on the 14th, Major Armistead would order the foul weather flag down and the garrison flag raised in victory, demonstrating to the vanquished British forces and the citizens of Baltimore that the fort withstood the onslaught, and that the Americans had won the day. It was at that moment that Francis Scott Key, eight miles out in the harbor, penned his poem, “Defence of Fort M’Henry.”

There are some scholars and others who contend that the foul weather flag was not in service during the battle. Many of these claims are predicated on assumptions that Major Armistead would not have flown a smaller flag on such a momentous occasion as the attack on Baltimore, regardless of the weather. Armistead specifically ordered a flag for the purpose of using it during foul weather so that the garrison flag would not be damaged or destroyed; there is no reason to believe, nor evidence to suggest, that he would not have ordered the foul weather flag be raised on that fiercely stormy night. In fact, there are recorded witness testimonies from British and American participants attesting to the presentation of both flags during the assault. One such witness was Pvt. Isaac Monroe (editor of the Baltimore Patriot) of the Baltimore Fencibles, who reported, “our morning gun was fired, the flag hoisted, [and] Yankee Doodle played. . . ”

William McPherson’s “Star Spangled Banner”

The historical record provides ample evidence supporting the presentation of the “Star Spangled Banner” currently housed in the Smithsonian Institution as the flag that Francis Scott Key, the participants of the assault and defense of Fort McHenry, and the citizens of Baltimore saw on the morning of 14 Sep 1814. But what of the flag that William McPherson owned and claimed to be the genuine artifact?

While the record shows that the Smithsonian flag is the one that flew over the fort that morning, it does not wholly support the claim in some corners that it was the flag that flew throughout the assault on the fort during a night of severe rainstorms. It does however lend support to the claim made by McPherson that he in fact owned the real “Star Spangled Banner.” But what of the exaggerated dimensions of the flag first reported in his obituary and funeral review in the Baltimore Sun on the 28th of June 1878? Was this just speculation on the part of the reporter who may have read about the historic flag previously, a mistake on his part, or was it gleaned from members of McPherson’s family? How does a 30’ X 42’ flag morph into such an enormous size?

One need look no further than William’s obituary and funeral tribute to surmise that the author, or a member of McPherson’s family most likely misread a previously published description of the flag; the original, “30 ft” X 42’ became “60 ft” X 42’, a very plausible explanation. The flag had been publicly displayed on many occasions in the years following the war to include the 1834 memorial service for the Marquis de Lafayette at the Baltimore Athenaeum, numerous Defenders Day celebrations, and the Whig Party convention of 1844. Col. Armistead’s daughter Georgiana (Armistead) Appleton would inherit the flag after her mother Louisa’s death in 1861 and would allow the flag to be displayed at various civic engagements.

Appearing in his obituary and in subsequent newspaper articles over the years, including his second wife Hannah’s obituary in 1902, is the statement that he would “festoon the front of his house” with the flag on each of the national holidays, and sit smoking his pipe while regaling his guests with stories of the old fort and the Battle of Baltimore.

It is important to emphasize the size of the 30’ x 42’ Star-Spangled Banner sewn by Mary Pickersgill as well as the dimensions of the storm flag at 17’ by 25’ relative to the size of the size of the flag described in McPherson’s obituary and the displaying of that flag on his house at times of national celebration. Mount Clare is the largest known house that William McPherson is known to have lived in, it is 46 feet wide and about 25 feet high at the roofline. This configuration, while large enough, would not uniformly support the displaying of a flag the size of that which Mary Pickersgill and her assistants produced, let alone one so large as described in William’s obituary; but it “most certainly would” support a full display of a flag measuring 17’ X 25’, the long ago “lost storm flag” that flew over Fort McHenry during the stormy night of 13 Sept 1814.

There is no known record of the size of his home in the Catonsville area where he lived in the years subsequent to his time at Mount Clare, but a modest farm home at that time would support the displaying of a flag the size of the storm flag. On the 1860 census, the value of William’s real estate was given as $15,000 with a personal estate of $4000, suggesting that he was somewhat well-off and most likely owned a very comfortable, and perhaps sizable home.

At the time of his death, the flag in William’s possession is described as having been reduced in size to “40’ X 18’,” or 18’ X 40’ if described as had been typically, a very curious and odd size indeed. This would suggest that 12’ of the flag would have been removed from the width or height, while only 2’ from the length, a reduction in size that would most definitely have presented noticeable distortion to the flag and rendered it unsuitable for respectable display. Is it possible that the reported measurement with respect to its length was again misstated by the newspaper reporter or a family member while compiling William’s obituary and that the dimensions are in fact more in line with those of the storm flag? We are also left with the question, would someone who “treasured” such an historic artifact as William McPherson did with what he believed to be the Star Spangled Banner go so far as to remove roughly 1600 square feet for souvenirs? That simply isn’t logical.

So, how did William McPherson come into possession of such an historic artifact? There is no known documentation as to how he may have obtained it, but the order-of-battle places McPherson and his regiment at Fort McHenry before and during the bombardment, so the proximity of his outfit presents several plausible options. Perhaps Sgt. McPherson was put in charge of a cleanup, medical aid, supply, or other detail that put him in a position to “scavenge” the discarded storm flag. He may have traded for it, or he may have even absconded with it, though that is unlikely given its size and bulk.

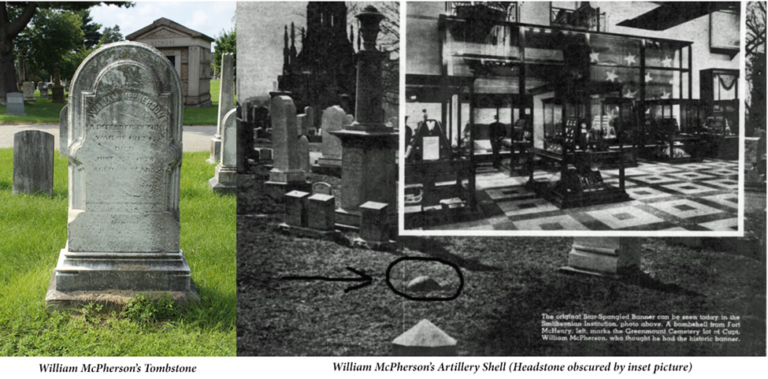

It is important to note as well that William McPherson also left Fort McHenry with a 150+ pound British artillery shell that he eventually had placed at the foot of his grave in Green Mount Cemetery, so he was not only a souvenir hunter, but an astute one at that, he knew the importance and value of the artifacts he sought to obtain. The artillery shell would “disappear” sometime after a 1953 Baltimore Sun article on McPherson and his flag. Some have proffered that he may have received a large flag as a gift from units participating in one of the rendezvous held at the Mount Clare House in the 1840s, there is no known record of such a gift and no mention of any over-sized American flag presented or displayed during these events.

The Smithsonian Garrison Flag

Though exactly when Lt. Col. Armistead acquired the Garrison Flag is not known, it is generally assumed that he most likely secured it shortly after the battle to keep as a memento; he would remain in command of the fort until his death in April of 1818 at which time, his widow Louisa would take possession of the flag, loaning it out from time-to-time for special occasions. When Lousia died in 1861, the flag would pass to their daughter Georgiana who, though recognizing its significance to history and to her family, would periodically lend it to selected civic engagements.

When Georgiana died in 1878, her son Eben Appleton would inherit the flag. In 1907, Eben would present the flag to the Smithsonian under an open loan agreement so that the public could view it and learn about the history of the flag and its important role in American history. In 1912, he would make the loan permanent by gifting the flag to the nation; writing sometime later, “It is always such a satisfaction to me to feel that the flag is just where it is, in possession for all time of the very best custodian, where it is beautifully displayed and can be conveniently seen by so many people.”

When visiting the Smithsonian, it is very apparent that this treasured national artifact has suffered significant damage over its two-hundred-year history. Aside from the natural age-related deterioration of the cloth itself, the banner displays areas of damage that have often led to spirited debate among the learned historian and academic communities as well as among the curious sleuths and armchair historians over the many years.

The Armistead’s, like many caretakers of historic artifacts, would receive numerous requests for cuttings from their historic banner. They would, however, limit their gifts to government officials, veterans, and others of importance. In the end, the famous banner would ultimately shed a bit over two hundred and forty square feet.

Two very distinct areas of damage to the flag have been at the forefront of controversy in many corners for years, but each has a logical explanation as to their cause. The first, a large hole nearly center at the edge of the blue field and into the stripes has been claimed as evidence of a cannonball or artillery shell piercing the flag, thus proving that this flag did indeed fly throughout the bombardment. It is generally accepted, as long ago as the 1880s, that the hole was a cutting of the “15th Star” given to President Lincoln, Jefferson Davis, or some other dignitary and may well be sitting in a private collection or buried in an attic of some obscure descendant who has no inkling of the significance of what they may have; or it may simply have been destroyed generations ago.

The only reasonable hypothesis with respect to the large hole being the result of a projectile would be that of a Congreve Rocket launched from the Erebus tearing through the flag, but that projectile would most likely have left a large area of scorching, if it hadn’t incinerated the flag completely, though the rains of the heavy storms could well have prevented that. However, it has been documented that these rockets, though launched by the hundreds, did not reach the fort as the Erebus could not get close enough and they fell into the harbor; artillery shells and cannonballs raining down from above would most likely just graze the soft, wet material flapping around in the winds of the storms.

The second area of controversy involves dark markings on the flag that some purport to be evidence of burning or heat scarring from shrapnel. However, testing and subsequent analysis has proven those marks to be a result corrosion from iron, such as the buckles on straps used to bundle and secure the flag during storage or transport.

There is no debate that the worn and tired old banner that rests today under special care and conservatorship in the Smithsonian Institution is the “Grand Old Flag” seen on that morning of 14 Sep 1814, sending chills of immense pride surging throughout the ranks at Fort McHenry and surrounding fortifications, cascading over the citizens huddled on the rooftops of Baltimore, and that so inspired Francis Scott Key to pen the words that would one day bind a nation together with pride in times of peace and in conflict.

But, what of Sgt. William McPherson and his claim that he alone possessed “the actual” Star-Spangled Banner? Were the attendees at his funeral, “Old Defenders,” Odd Fellows, and others mistaken in what they witnessed? No subsequent articles in the ensuing years, letters-to-the-editor, or other works refuting what transpired on that day in June 1878 at Green Mount Cemetery have been revealed, so…

“Busted, or Plausible?”

Author: Lyle Garitty

Sources:

- Smithsonian Institution

- The Baltimore Sun

- National Park Service

- Sundry military and historical works